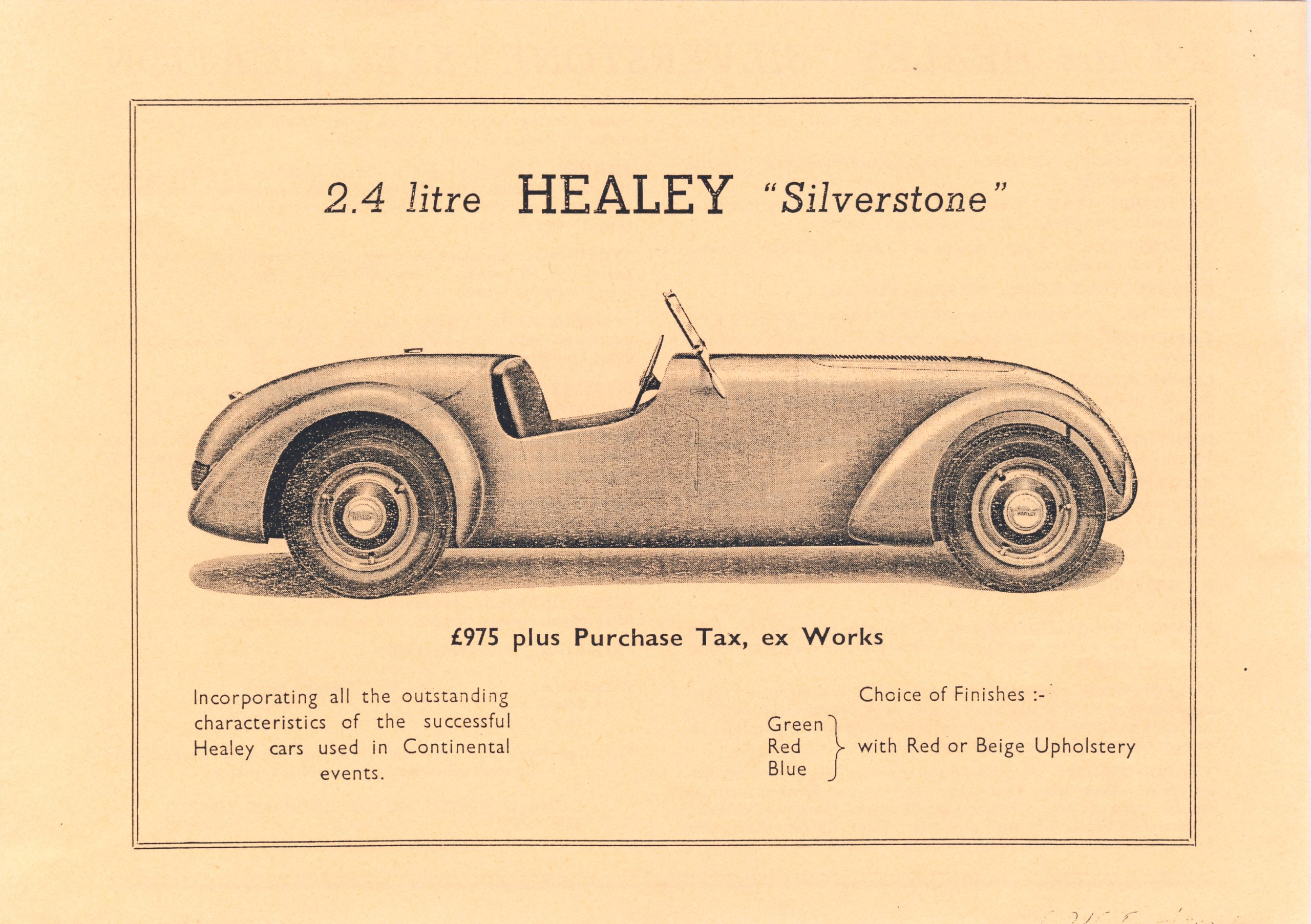

Healey Silverstone Story

Autor Bernd Sgraja

Donald Healey introduced his first car with the Healey badge in 1946. He had built it in The Cape, in the English country town of Warwick.

Healey, a native of Cornwall, had earned a considerable reputation as a successful racing driver in the 1920s, which made him interesting for the Midland car industry in the 1930s as a consultant, chief designer and technical director.

It was his firm conviction that a competitive test for the man on the road was always the right basis for the presentation of a product and the performance of a car, safe driving and handling should always be the main qualities of the cars, whom Healey had worked or who later bore the name Healey.

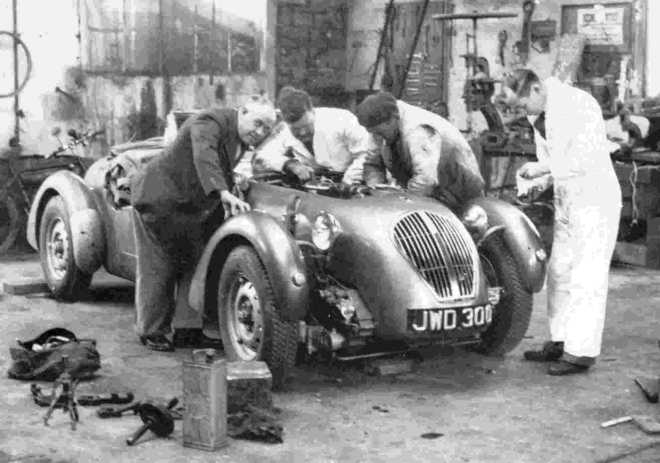

These principles were implemented in the first Healey of 1946, the Westland. Donald Healey set to work with a team of specialists.

There were:

Ben Bowden – Body Designer,

Sammy Sampietro – Chassis Engineer,

Victor Riley – from his production, motor, transmission and rear axle,

Wally Ellen – working space,

Peter Shelton – he built the body of the first Healey Prototype,

James Watt – Sales Manager and

Roger Menadue – Experimental Engineer.

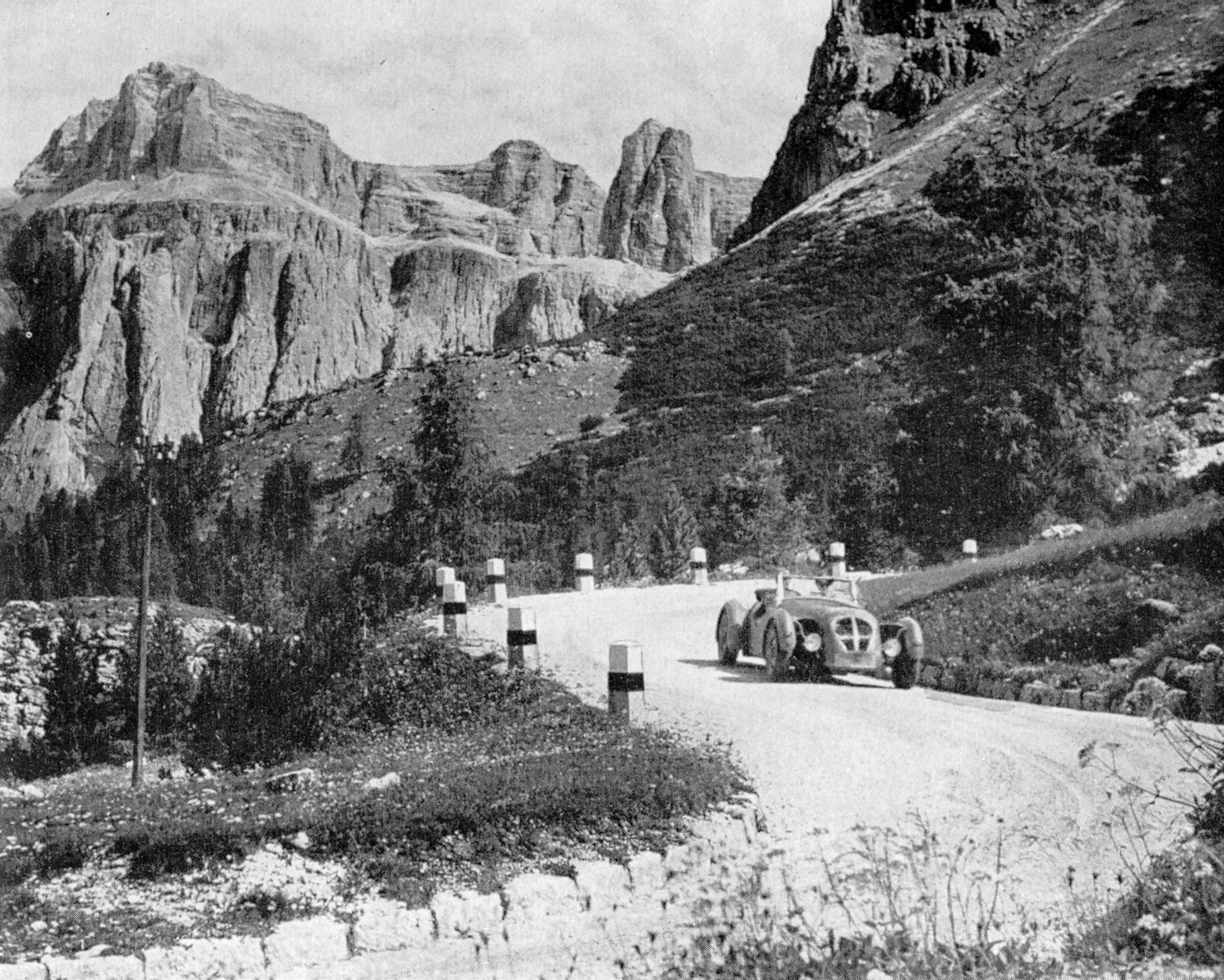

Two years later, Healey’s eldest son Geoff finished the Mille Miglia as a remarkable overall ninth with a Westland roadster prepared at the Warwick plant, while Count Johnny Lurani and Guiglelmo Sandri in an “Elliot”, the four-seater Gran Tourismo limousine version of the Westland, the category production cars won.

In 1949 Geoff returned to the Mille Miglia with the well-known English automobile journalist Tommy Wisdom with his Westland and won the touring car class in a new record time with two minutes advantage over his next chaser. Healey’s first hard-fought success was a class victory, at the same time the highest ranking of a British vehicle, at the Alpine Rally, which was followed by many more trophies for the trophy cabinet, while in the following years private riders took their share of ” Silverware” for the local chimney sim.

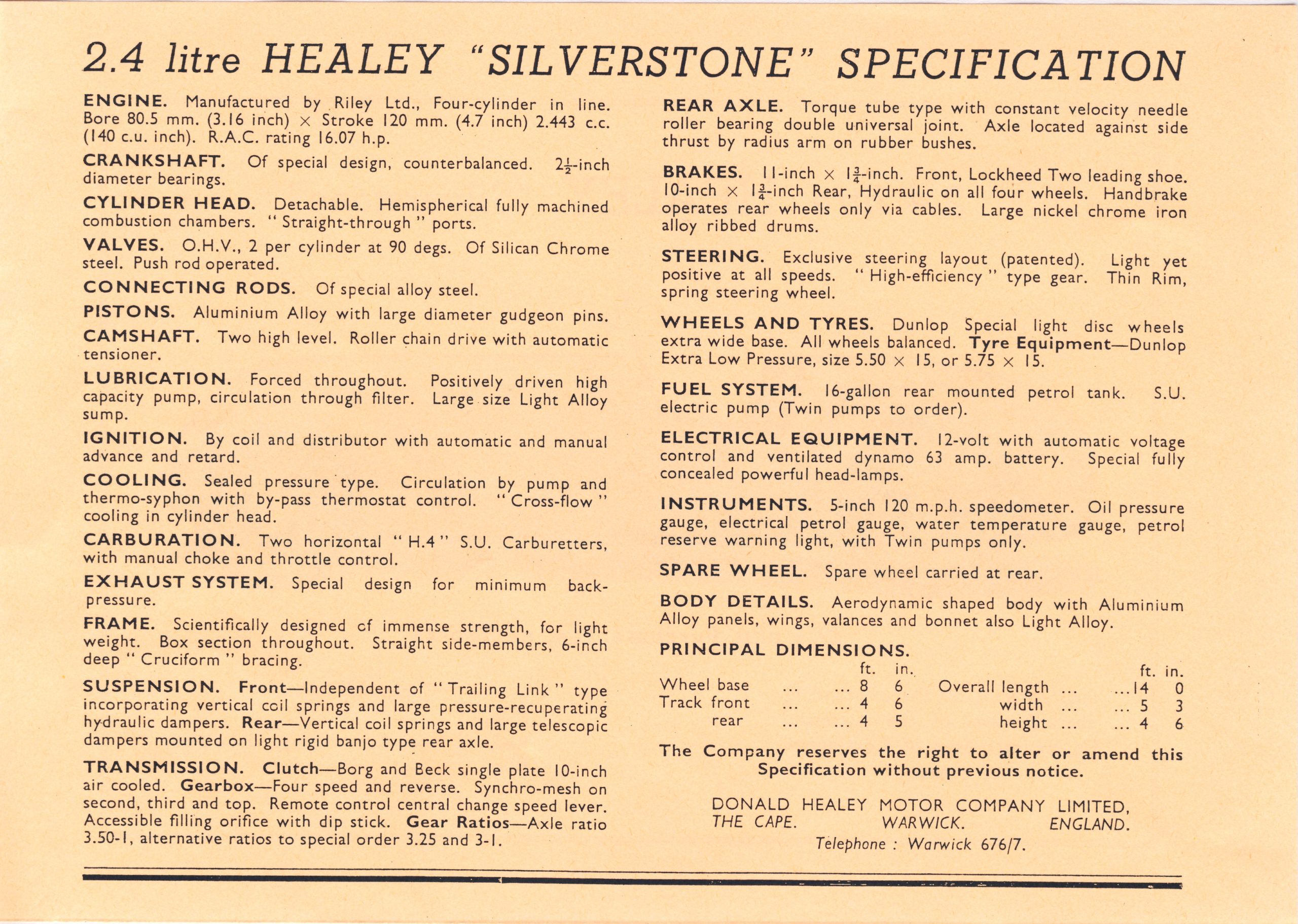

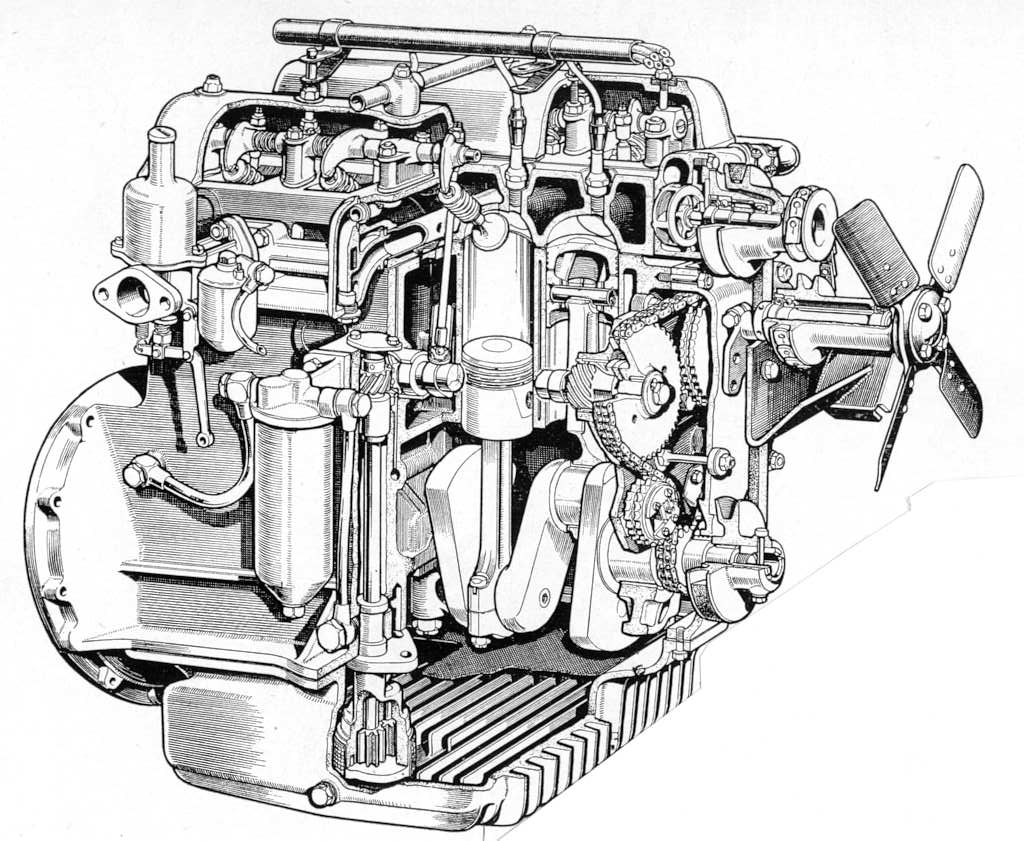

The anatomy of the Silverstone was based on a robust cross-edged chassis, made of 18-gauge steel sheet, with light but strong 15 cm deep lateral longitudinal beams in U-shape with legs angled at the end [“top hat” section]. Slightly modified, it allowed the engine to be moved backwards by 203 mm [8 inches] and with further modifications it was possible to mount a 72.5 litre [16 gallon] petrol tank. The chassis weighed about 59 kilos. The original Healey chassis was a hugely successful design and remained basically the same for all Healey models built until 1954, with the exception of the Nash-Healey, which had a longer wheelbase.

Healey Elliott 104

Healey Westland 70

Healey Sportsmobile 25

Healey Silverstone 105

Healey Duncan 92 on three body variants

Healey Abott 88

Healey Tickford 225

Nash Healey 104

Alvis Healey / Healey Sportsconvertible 28

Plexiglas wind repellent, improved top design, cockpit cover and chrome-plated front bumper with horns became fashionable and were also delivered.

Silverstone production amounted to 51 “D” types followed by 54 “E” types.

which fulfils its purpose and takes little consideration for comfort.

It is still, even today, a vehicle you drive because it’s fun to drive in an open, sporty, two-seat classic that is safe and fast, on the road as well as on the race track.

A swing arm design was chosen for the front single-wheel suspension, which allowed a precisely controlled vertical wheel movement, was well damped and resulted in minimal deviations in fall and forward running.

At first glance, it looks like a sledgehammer for nut-cracking, but on closer inspection it turns out to be light, strong and durable in operation.

It is also very service-friendly – the lightweight aluminium arm moves in large-sized needle bearings, which sit in a chassis-screwed case. Simple coil springs were used in conjunction with Girling piston shock absorbers. In addition, a stabilizer was mounted.

Like many small series manufacturers, Healey used many rapidly available components on the market, a typical process used at the time in the construction of suspension systems.

The Silverstone rear suspension consisted of a Riley axle with shortened cardan shaft, simple coil springs and Newton Bennet telescopic shock absorbers.

The lateral guidance of the axle was carried out by a panhard rod made of aluminium tube.

It must be said that the mention of each individual specification point in this article refers to the original delivery condition of the Silverstone upon delivery from the Warwick factory. Many of the Silverstones that still exist today have undergone changes in the over 60 years due to accident repairs, total restorations and competitive modifications, or have the wishes of the owners of their original “Warwick” specification or the appearance is changed.

What can you expect from a Silverstone in good condition today?

Surely it brings at least its earlier performance, if not a bit more, considering the improvements in lubricants, fuels and tyres. Both models weighed about 18 cwt. Under average conditions, the direct gear ranged from 10 to over 100 mph. The acceleration time from 0 to 60 mph of about 11 seconds corresponded to a time of 17 seconds for the standing quarter mile and the maximum was sometimes above, sometimes below 110 mph according to the vehicle and the conditions. Its direct-gear pull-through capacity is sufficient for most driving situations and its trouble-free driving behaviour allows relaxed driving even at today’s traffic density. Its weight distribution, engine, transmission, driver and passenger sit between the axles, results in a balanced driving balance and stability. This basic solidity originated from the solid chassis. Its slightly appealing suspension and controlled direct steering made his driving, handling and directional stability far better than that of most contemporaries.

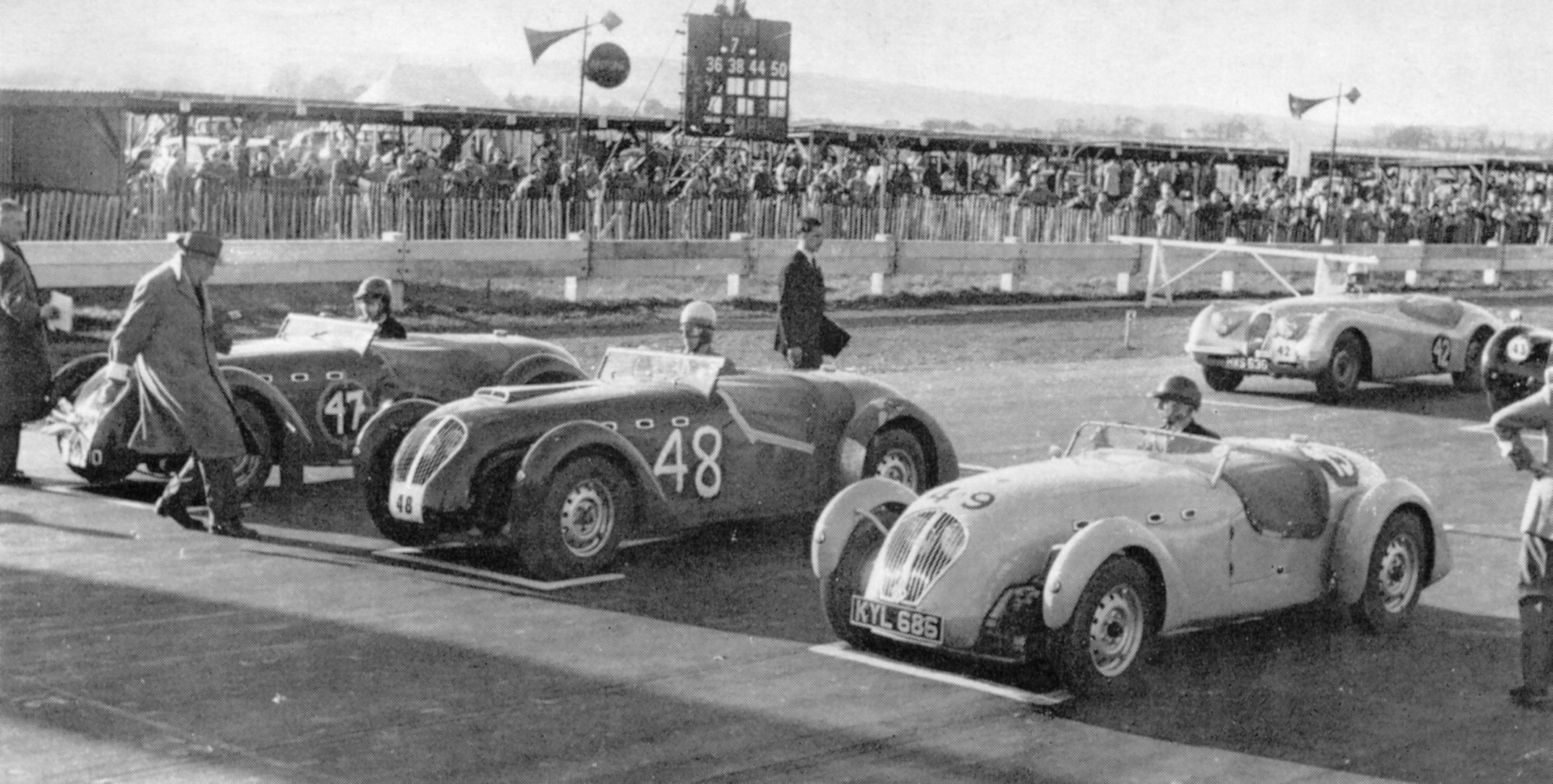

The Production of the Silverstone ended after 105 units, And Healey became increasingly involved in the production and promotion of the dollar-producing Nash-Healeys. To the glory of its predecessor, the 4.1-litre Nash machine, built into an extended chassis variant of the Silverstone, proved to be a combination that proved successful in Le Mans. The cars with a body that included the wheels here, under Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt, finished fifth overall at Le Mans in 1950, sixth overall in 1951, and in 1952 Leslie Johnson and Tommy Wisdom finished third overall behind two Factory Mercedes.

The size of the Healey organization allowed for business flexibility that did not enthimude the giants of the automotive industry. The regulations in the racing class, amended in 1952, no longer allowed car bodies with free-standing fenders / cycle wings. This meant the end for the Healey Silverstone as well as for the Allard J2.

The combination of the attractive Nash-Healey project and the growing competition in the market undoubtedly influenced Healey’s decision to discontinue Silverstone production. Although the base price of the Silverstone was less than 1000 pounds, with the purchase tax the final price was only 20 pounds lower than that of the Jaguar XK 120, which was offered stronger, more sophisticated and as a more universal sports car with alternative body variants … With an existing dense dealer network worldwide, the Nash-Healey was ready to take on the challenge on behalf of the Warwick company.

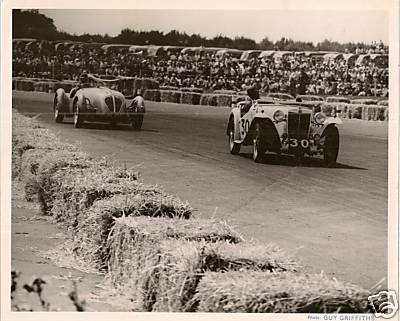

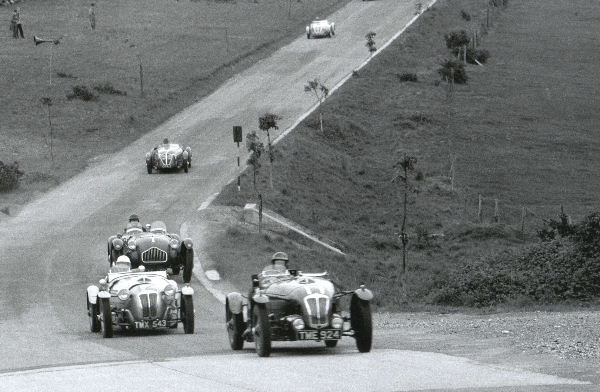

Many owners and competitors around the world have played an important role in the history of the 105 Silverstones. Understandably, considering that of all the Healey models of the Silverstone was built exclusively for the enthusiastic Clubman, who wanted a very uncomplicated, easy-to-maintain, competitive sports car “off the shelf”. Look around and you’ll find that there are still a lot of silverstones who are doing a good job in club races, rallies, mountain races and slaloms.

Perhaps the best known Silverstone private drivers are Charles and Jean Mortimer. In particular, it is worth remembering Charles’s book “Racing a Sports Car” that deals extensively with the use of the Healey Silverstone, chassis number D 2, registration number OPA2, driven by the Mortimers, during the 1950 racing season. It is worth noting that Jean Mortimer successfully asserted herself as a woman in this male domain.

Email Me